Our seed saving series outlines the techniques and methods needed to save seeds in your garden.

Contents:

While nearly any plant in your garden will produce seeds if left to reach maturity, not all plants make good candidates for seed saving. In particular, some classes of plants will produce unreliable results in future generations, not necessarily staying true to the original variety's characteristics.

But how do you know which seeds are the best to save? For the answer, we need to take a quick look at some of the botanical basics of how plants are fertilised and how they set seed.

Types of Flower

Before setting seed, plants produce one of two types of flower. The first and most common type is known as a ‘perfect’ flower. Perfect flowers contain both male and female parts, making the plant capable of self-pollination. Fertilisation usually happens through a breeze passing pollen from the male to female parts within the same flower, or between flowers on a single plant, although pollination by insects or birds is also possible.

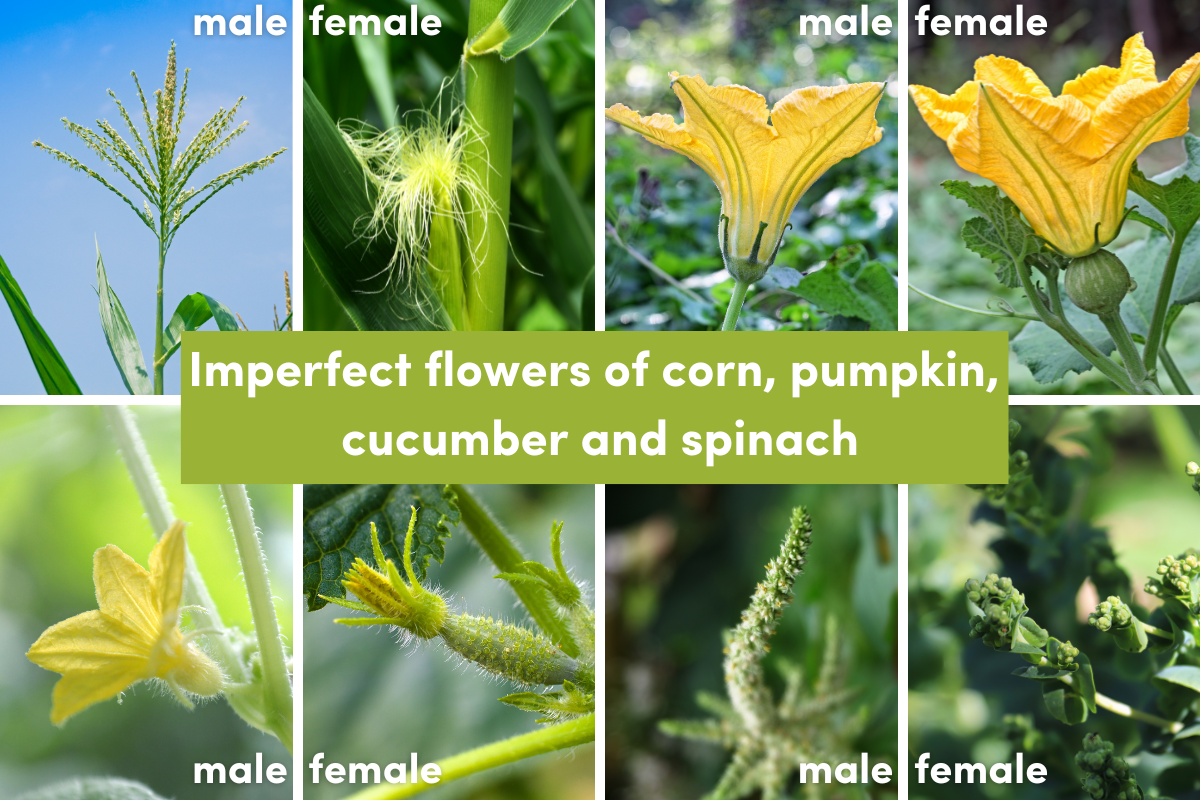

The second type is an 'incomplete' flower, which is either male or female, and pollination needs to be done by wind, insects or humans. Some plants, called monoecious plants, produce both male and female flowers on the same plant. Others, called dioecious plants, produce either male or female flowers on each plant.

Knowing about flower types is important for seed saving as it gives gardeners an indication of how many plants are needed to pollinate flowers and produce seeds. The type of flower and its pollination method also determines the actions gardeners need to take to avoid accidental cross-pollination from plants of the same species.

For example, self-pollinating plants, also known as inbreeders, include lettuce, tomato, okra, peas and beans. These plants will happily produce seeds from a single plant with little or no attention from the gardener. With most of the pollination being done from a single parent, the resulting seeds will mostly stay true to type.

On the other hand, plants with incomplete flowers are known as outcrossers, and include onions, carrots, parsley, celery and brassicas. These plants are pollinated by wind, insects or humans, and in doing so they receive a mix of genes from two parents. This results in greater genetic diversity but also increases the risk of a plant deviating from its variety in the next generation. Gardeners wanting to save seed from outcrossers will need to grow a larger number of plants and take action to avoid accidental cross-pollination.

The Issues of Relatedness and Cross-Pollination

The wide range of vegetable patch varieties available today spring from a surprisingly limited number of species. Two plants could show very different appearances and fruiting patterns, thanks to the effects of decades or centuries of selective breeding, yet still be part of the same botanical species. Perhaps the best example of this is found in the brassica family, with broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, kohlrabi and Brussels sprouts all being examples of the species Brassica oleraceae.

By definition, plants of the same species can breed together through pollination, and the resulting seeds will contain a genetic mix of the two parent plants involved. This may mean your seeds don't reflect the characteristics of the plant they grew from, with the next generation potentially showing markedly different qualities.

To find the botanical species of a plant, look on the seed packet in the first two words of the botanical name. For example, the botanical name of broad bean is Vicia faba. The botanical name of cauliflower is listed on the seed packet as ‘Brassica oleraceae botrytis’, so its botanical species is Brassica oleraceae as only the first two words determine the species.

If you're growing two or more varieties of the same species for seed saving you'll need to take a few extra measures to protect the seed purity (see article three in this series).

Avoid F1 Hybrids

If your favourite plants are hybrid varieties there's no way of escaping the yearly seed-buying cycle. Hybrid varieties are denoted by an 'F1' on the seed packet and are created by the controlled breeding of two parent varieties by the seed producer.

Unfortunately, many hybrid varieties are sterile and their seed is useless for cultivation. And while some hybrid plants can grow to set viable seed, future generations are highly unlikely to grow true to the original plant. Each seed contains a random genetic mix of the two parent varieties used for breeding, and the final characteristics they'll develop are almost completely unpredictable, making seed saving a thankless exercise.

The Plant's Life Cycle

Lastly, the life cycle of a particular plant species is also a vital factor in planning your seed saving. The best choices are usually annual plants, such as tomatoes, beans, cucumbers and so on, which produce a new set of seeds every year.

When deciding which seeds to save, think about the amount of time it'll take to produce seeds, even for annual species. Many veggie patch staples are never grown through to the flowering and seed producing stages. The 'days to maturity' figure on seed packets refers to the harvest time, and growing mature seeds may take weeks longer. If your growing season is already tight, saving the seeds of some species might not be viable.

Biennial species like carrot, parsley and onion won't flower and set seed until their second season. This means the seed saving process is a more lengthy one and so not necessarily ideal for beginners.

And lastly, while seeds can be saved from many perennials which flower every year, the long life of these plants means that seed saving isn't as important, and for many plants, taking cuttings is a better way of producing reliable results.

Bearing all these points in mind, some seeds are easier to save than others. In general terms, annual plants that are self-fertile and produce dry fruit, such as peas and beans, are easy to save and a good option for beginners.

The more potential for cross-pollination there is, the more unpredictable the results will be, and so saving seeds of vegetables such as corn, turnip and Brussels sprouts is more challenging. Nonetheless, there are ways to make even these more difficult vegetables easier by isolating them during the pollination phase, as the next part in this series explains.